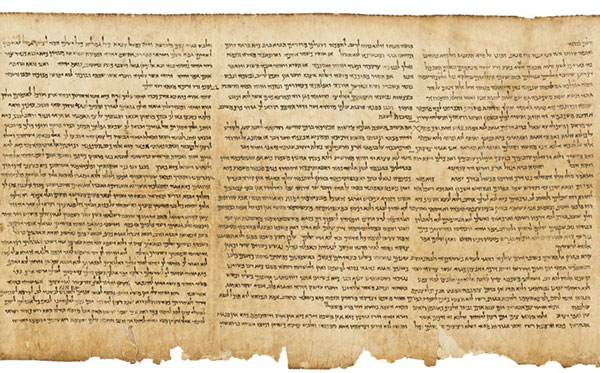

The Dead Sea Scrolls were first discovered in late 1946 in caves along the Dead Sea. The ancient settlement of Khirbet Qumran held millennial old sealed clay jars which contained about 1200 manuscripts, including more than 300 Biblical texts. Arguably the greatest discovery at Qumran is the Great Isaiah Scroll, a nearly complete scroll that was copied around 125 BC. It contains all 66 chapters of Isaiah.

In this book, we will focus on a particularly interesting passage in the second half of Isaiah: chapter 53. It has been called the Holy of Holies of the Old Testament. These twelve verses offer a summary of the entire New Testament, written more than 700 years before Jesus Christ was born. A number of passages in the Hebrew Scriptures describe the victory of the Messiah as the ruler of the world, and the Jews have focused on those. This chapter provides another unexpected purpose for the great King; it’s an incredible prophecy that describes the Messiah as a servant who suffers and dies for His people.

Isaiah’s Writing

The Book of Isaiah opens with a declaration of its authorship. In verse 1:1, the prophet Isaiah, son of Amoz, states that he wrote his prophecy during the reigns of “Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah, kings of Judah.” Chapter 6 of Isaiah describes a vision that took place “in the year that King Uzziah died,” — about 740/739 BC.[1] Isaiah volunteers to be a prophet in this passage, and the LORD gives him a dismal task:

And he said, Go, and tell this people, Hear ye indeed, but understand not; and see ye indeed, but perceive not. Make the heart of this people fat, and make their ears heavy, and shut their eyes; lest they see with their eyes, and hear with their ears, and understand with their heart, and convert, and be healed. Then said I, Lord, how long? And he answered, Until the cities be wasted without inhabitant, and the houses without man, and the land be utterly desolate, And the LORD have removed men far away, and there be a great forsaking in the midst of the land.

— Isaiah 6:9–12

Throughout Isaiah, the heart of God cries out to the hard-hearted people of Judah. He alternates back and forth between rebuke and comfort, rebuke and comfort. Meanwhile, Isaiah offers some of the most profound prophetic passages in all of Scripture, describing the future sometimes years, centuries, and even millennia in advance.

The majority of Isaiah gives us a rich variety of poetry. Wisdom poetry and hymns of rebuke, prediction and prophecy pour at us from chapters 1–35. We then find a change in pace at chapters 36–39, where Isaiah turns to prose. During this “bridge,” the prophet gives an interesting historical narrative describing important events during the reign of King Hezekiah. Then, at chapter 40, the poetry of comfort, prediction, and rebuke picks up again until the end of the 66 chapters.

Right in the center of this second part, we find the focus of our present study: Chapter 53. It is located 13 chapters from chapter 40 and 13 chapters from chapter 66. The Bible’s chapter divisions were not in the original; they were placed in the New Testament in the 13th century AD and in the Hebrew Old Testament in the 15th century, but the chapter breaks often follow thematic breaks in the text.

I like to follow the Holman Bible Commentary and further divide chapters 40–66 into three parts:[2]

- The Purpose of Peace: 40–48

- The Prince of Peace: 49–57

- The Program of Peace: 58–66

The second subsection on The Prince of Peace is bookended by essentially the same verse. Isaiah 48:22 states, “There is no peace, saith the LORD, unto the wicked.” Isaiah 57:21 repeats this sentiment, saying, “There is no peace, saith my God, to the wicked.” This gives us natural section divisions:

- The Purpose of Peace: 40–48

- “No peace for the wicked” 48:22

- The Prince of Peace: 49–57

- “No peace for the wicked” 57:21

- The Program of Peace: 58–66

In the middle of this second section, we find chapter 53. I’m calling it the Fulcrum of the Entire Universe. That might sound a bit heady, but this passage truly is the pivot point of all history. While Isaiah 9:1–7 or 11:1–10 describe the glorious future reign of the Messiah, this powerful chapter toward the end of the book gives a much different picture. Here we find the Messiah as a sacrifice who suffers to pay for the sins of the people.

The two ethnic roots of Judaism are actually divided over Isaiah 53. The Ashkenazi Jews were so disturbed by this chapter that they removed it from their Bible altogether. The Sephardic Jews thankfully left it in. When the Dead Sea Scrolls were found, the Great Isaiah Scroll included Isaiah 53 with all its unhampered power. What’s more, it dates to the second century before Christ was born, demonstrating the existence of these verses in the book of Isaiah long before Jesus entered history and died.

The Israeli Museum has a special building dedicated to the Great Isaiah Scroll, and Isaiah 53 cries out from it. The original book of Isaiah was written over the course of Isaiah’s adulthood between 740 and 686 BC, long before many of the events it describes in advance occurred. This passage is so important that it is cited in all four Gospels as well as Acts, Romans and 1 Peter.[3] What makes it so important? The crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

Crucifixion

We know that crucifixion was not invented until the Persian Empire, after which it was widely adopted by the Romans.[4] The official form of execution in Israel was stoning. It’s particularly startling, therefore, to find the crucifixion of the Messiah detailed in Isaiah centuries before this form of execution was invented.

Psalm 22 is another important passage that describes Jesus’ death from the viewpoint of Christ hanging on the cross. His unbroken bones, His thirst, His pierced hands and feet, His humiliation and ridicule, and even the gambling done for His clothes are all described by David in Psalm 22, nearly 1000 years before the crucifixion took place. Zechariah 12:10 adds to the picture, declaring, “They shall look upon me whom they have pierced,” offering a description by the LORD of those who will see Him at His return.

Here in Isaiah 53, we find the purpose of Christ’s death written centuries in advance. Isaiah is a supernatural book, and this is a supernatural passage.

Deutero-Isaiah

Who hath believed our report? And to whom is the arm of the LORD revealed?

— Isaiah 53:1

It is popular these days to split Isaiah into two parts, crediting the authorship of the first 39 chapters to Isaiah, son of Amoz, and chapters 40 to 66 to an entirely different person (Deutero-Isaiah), who lived hundreds of years later. The first part of the book is seen as a series of warnings and rebukes made by the original Isaiah, while the last part is seen as a series of comforting passages made by Deutero-Isaiah after the Babylonian captivity.

It is a fact that the Book of Isaiah describes events that took place long after the death of Isaiah, son of Amoz. Secular historians and Bible critics have dismissed these prophetic passages as written after the fact. They do not recognize Isaiah’s divine inspiration; they presume that somebody else wrote those prophetic verses after they took place.

Hastings Bible Dictionary quotes biblical critic A.B. Davidson’s summary of secular thought about prophecy:

The prophet is always a man of his own time and it is always to the people of his own time that he speaks, not to a generation long after, not to us. And the things of which he speaks will always be things of importance to the people of his own day, whether they be things belonging to their internal life and conduct, or things affecting their external fortunes as a people among other peoples.[5]

Isaiah doesn’t obey A.B. Davidson’s ideas about the purposes of prophecy. He doesn’t just prophesy to the families of Judah, and he doesn’t just speak to the people of his day. He cries out the words of God to the many lands surrounding Judah — and unto the whole world.[6] He declares that he speaks to future generations:

Now go, write it before them in a table, and note it in a book, that it may be for the time to come for ever and ever:

— Isaiah 30:8

Isaiah prophesied from about 740–686 BC. The Kingdom of Israel in the north was conquered by the Assyrians in 722 BC, and we find in Isaiah 36–37 that the Kingdom of Judah nearly suffered the same fate. God protected Judah from its enemies because faithful King Hezekiah of Judah trusted in the LORD. It would take several more generations for Judah and its capital at Jerusalem to fall to Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon in 586 BC.

Yet, Isaiah does not focus much on Assyria, the enemy of his day. He repeatedly speaks of the future, about the rise and fall of Babylon.[7] He describes long in advance the ascent of the Persian Cyrus the Great, whom the LORD calls by name in Isaiah 44:28–45:6. “That saith of Cyrus, He is my shepherd,… That they may know from the rising of the sun, and from the west, that there is none beside me. I am the LORD, and there is none else.”[8]

Through His prophet Isaiah, the LORD constantly speaks of the distant future. He does this as a sign of His eternal power, because He knows the stubbornness of His hearers:

I have declared the former things from the beginning; and they went forth out of my mouth, and I shewed them; I did them suddenly, and they came to pass. Because I knew that thou art obstinate, and thy neck is an iron sinew, and thy brow brass; I have even from the beginning declared it to thee; before it came to pass I shewed it thee: lest thou shouldest say, Mine idol hath done them, and my graven image, and my molten image, hath commanded them.

— Isaiah 48:3–5

There are a variety of external and internal facts about Isaiah that point to a single author.[9] Jewish tradition has always attributed the book to Isaiah alone, and in the Dead Sea Scrolls we find the Great Isaiah Scroll has no division at all after chapter 39. It is a single large scroll, completely credited to Isaiah, son of Amoz. In his book The Unity of Isaiah, Oswald Allis jokes, “Obviously the scribe was not conscious of the alleged fact that an important change of situation, involving an entire change of authorship, begins with chapter 40.”[10]

The writing of Isaiah is among the best, most beautiful and skilled poetry in all the ancient world. This excellent writing skill continues from chapter 1 to chapter 66. What’s more, we see no Babylonian influence in his vocabulary. In the post-exilic books of Esther, Ezra or Nehemiah, we find a range of Babylonian vocabulary and idioms, but Isaiah contains only pure pre-exilic Hebrew.

The subject matter in both halves of Isaiah is rebellion and idolatry, problems that had passed away after the Babylonian exile. The land of Israel described in Isaiah is the rocky, mountainous land of Israel and not the wide, flat land of the Fertile Crescent.

And they shall go into the holes of the rocks, and into the caves of the earth, for fear of the LORD, and for the glory of his majesty, when he ariseth to shake terribly the earth.

— Isaiah 2:19

Enflaming yourselves with idols under every green tree, slaying the children in the valleys under the clifts of the rocks?

— Isaiah 57:5

Isaiah constantly calls God, “The Holy One of Israel” throughout his entire book. It’s a name used in only six verses by other Bible writers. Isaiah uses it repeatedly, 12 times in chapters 1–39 and 14 times in chapters 40–66.

There are only a couple of reasons to split up Isaiah between two or more writers. The first is a distinct bias against predictive prophecy. Those who doubt God’s existence and deny His power will not accept the reality that God is the First and the Last, “Declaring the end from the beginning, and from ancient times the things that are not yet done.”[11] They refuse to believe that God spoke to Isaiah and told him things in advance. They therefore attribute the prophetic passages to other writers.

A misunderstanding of the purposes of prophecy might be a second reason to split up Isaiah. There are those like A.B. Davidson who force the prophet into a narrow box, relegating his words to the small groups of people around him. These critics will not accept that Isaiah wrote to distant peoples and future times, and they will feel obliged to credit other writers with Isaiah’s words to broader audiences.

Taken at face value, however, the internal and external evidence point to a single Isaiah who saw the throne room of the LORD and spoke to all of us from the heart of the eternal Godhead. We should not be surprised that Isaiah sometimes offers stern rebuke and then turns and speaks with comfort. His words are communicating to us from God, who hates the sins of His wayward people, but who loves them and longs to heal them just the same.

Bible critics invented “Deutero-Isaiah” for their own purposes, without solid evidence. It’s frankly irrational to suggest that one of the greatest, most skilled writers of all time just vanished from history. There was never even a hint of any other writer until modern scholars declared they knew better. Well before the time of the New Testament, all understood that Isaiah had written the entire book.

Who hath believed our report? And to whom is the arm of the LORD revealed?

— Isaiah 53:1

This is the first verse of Isaiah 53, and John quotes it in Chapter 12, verse 38 of his Gospel. He notes that the people didn’t believe Jesus even though He performed many miracles before them. He then quotes Isaiah 6:10, reminding us that the LORD told Isaiah their eyes would be blinded and their hearts hardened:

Therefore they could not believe, because that Esaias said again, He hath blinded their eyes, and hardened their heart; that they should not see with their eyes, nor understand with their heart, and be converted, and I should heal them. These things said Esaias, when he saw his glory, and spake of him.

— John 12:39–41

In one breath, John quotes from Isaiah 53, and in the next breath he quotes from Isaiah 6, crediting both to Isaiah.

It’s interesting that John quotes from the first and last parts of Isaiah in two breaths, attributing them both to Isaiah without any question. As a teenager, I ran into this, and I now regard John 12:39 as a treasure. That verse saved me hours of tedious library research. Here John cuts through it all. The Isaiah who wrote Isaiah 53 and the Isaiah who wrote Isaiah 6 are the same Isaiah, and those who do not believe are simply hardened. John is telling us — and the entire Bible is telling us — that there is only one Isaiah. Knowing this will save us all a lot of money buying nonsense commentaries that deny the power of God.

This excerpt is from Dr. Chuck Missler’s briefing pack The Fulcrum of the Entire Universe. Available in video, audio, and now Paperback and eBook formats.

Notes:

- Thiele, E. (1983). The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, 3rd Ed. Grand Rapids: Zondervan/Kregel, 217. ↩

- Clendenen, E. & Howard, J. (2015). The Holman Illustrated Bible Commentary. Nashville: Holman Reference, 710. ↩

- Matthew 8:14–17; Mark 15:28; Luke 22:35–37; John 12:37–41; Acts 8:26–35; Romans 10:16–21; 1 Peter 2:21–25. These are just the direct quotes of Isaiah 53 and do not include the many passages that describe Jesus fulfilling its prophecies. We will cover those in detail later in this book. ↩

- Retief, F.P. and Cilliers, L. (December, 2003). The History and Pathology of Crucifixion. South African Medical Journal: 93(12): 938–941. ↩

- As quoted in Allis, O. (1951). The Unity of Isaiah. (A study in prophecy.) (p. 2). Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock. ↩

- Cf. Isaiah 13–24 ↩

- Isaiah 13–14; 21:9; 39:1–8; 43:14; 47:1; 48:14, 20 ↩

- Isaiah 45:6 ↩

- See Allis, O. (1951). The Unity of Isaiah. (A study in prophecy.) (p. 40). Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock. Allis does a thorough job of answering critics who deny a single authorship of Isaiah. ↩

- Allis, O. (1951). The Unity of Isaiah. (A study in prophecy.) (p. 40). Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock. Allis does much better job of covering all these matters than I do in my little appendix jottings. ↩

- Isaiah 46:10 ↩