The five books of Moses are unquestionably the most venerated of texts the world over. Jewish sects all give the Torah highest honor, even if the sects can’t agree on anything else. Christians also hold the Torah in high regard, and Jesus repeatedly authenticated its five books by attributing them to Moses. Jesus quotes from the Torah more than any other portion of Scripture, and that should get our attention.

Every book of the Bible is precious. The entire Bible is supernatural, breathed by the Spirit of God for you and me. The Torah speaks to all of us, not just to people of Jewish background and not simply as an Old Testament background of the New Testament.

These 66 books are an integrated message system, a message penned by 40 different men over thousands of years, yet every detail, every word, every place name is there by the deliberate design of the Creator of the Universe. Once you begin to discover that for yourself (and not just because somebody like me says so), you find that the whole Bible ties together in an astounding, remarkable way. The Torah and the Prophets anticipate details of events that happened hundreds and thousands of years later. The entire book ties together. This tells us that the origin of this message is from outside the dimensionality of time itself.

The five books of Moses are Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. These first five books of the Bible are collectively called the Torah, or the Law. Sometimes scholars call them by the Greek term, the Pentateuch.

- Genesis is the book of beginnings.

- Exodus is the birth of the nation.

- Leviticus is the law of the nation.

- Numbers describes the wilderness wanderings.

- Deuteronomy gives Moses’ final messages.

Deuteronomy was given to the Israelites shortly before they entered the Promised Land under Joshua. It can be viewed as the bridge between the first four books, written outside the Land, and the next seven, written inside the Land. Throughout Numbers and Deuteronomy, the children of Israel are still wandering in the wilderness. After Deuteronomy, Joshua leads them into the Land. Jesus quotes more from the Torah than from any other portion of Scripture, but He quotes from Deuteronomy more than any other part of the Torah. This should underline this particular book for us.

The Documentary Hypothesis

In the 18th and 19th centuries, scholars began to deny that Moses actually wrote the Torah. Jean Astruc divided Genesis into two sources he believed Moses had used,[1] but others after Astruc argued that Moses hadn’t written any of it. It was argued that the Torah came together about the time of Solomon. These ideas were codified in the Documentary Hypothesis of K.H. Graf and Julius Wellhausen also called the Graf-Wellhausen hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, the Torah was just a collection of writings from four different sets of writers, designated the Jawhist (J), Elohist (E), Deuteronomist (D) and Priestly (P) sources.

Of course, these scholars had nothing to go on but their own opinions. They thought writing hadn’t existed during the time of Moses, and they saw stylistic differences that they thought distinguished one passage from another. They read into the text the “purpose” each of the J, E, D and P contributors had for writing their own parts of the text.

Textual scholar and professor Kenneth Kitchen denied the claims of the Documentary Hypothesis in 1966, writing:

Even the most ardent advocate of the documentary theory must admit that we have as yet no single scrap of external, objective evidence for either the existence or the history of J, E, or any other alleged source-document.”[2]

The archaeology of the 20th century showed us that writing was, in fact, common in the centuries before Moses. Solomon began building the Temple just 480 years after Moses,[3] and he moans that a multitude of books had been written by his time:

And further, by these, my son, be admonished: of making many books there is no end; and much study is a weariness of the flesh.

— Ecclesiastes 12:12

There are thousands of cuneiform tablets from the centuries prior to Abraham, cutting the legs out from under the assumption that Moses couldn’t have written the books that the Bible says he did. Still, the hypothesis was never based in actual evidence, but on an anti-supernatural bias and a skeptical view of the Bible. The Old Testament, from beginning to end, consistently attributes the Law to Moses.[4]

It’s not remarkable that the Torah — written by Moses who spoke to God face-to-face[5] — was carefully copied and handed down generation after generation. Obviously, Moses did not write about his own death in Deuteronomy 34. Deuteronomy is a record of the words that Moses spoke to Israel, which suggests that it was taken down by Joshua as Moses spoke. It seems that Joshua served as Moses’ scribe at times,[6] and it’s likely that he wrote Deuteronomy’s final chapter. He went with Moses onto the mountain of God and into the Tabernacle, serving God faithfully, being himself filled with the Spirit.[7] The bottom line is that these five books are the product of Moses, whether or not his servant Joshua finalized the book by telling us about his death.

The most foolish thing about the Documentary Hypothesis is that it’s a denial of Jesus Christ. Jesus quotes from each of the books of the Torah and attributes them to Moses, so if Graf and Wellhausen were correct, then Jesus was wrong. Take your pick. If you don’t believe in Jesus Christ, then you’ve got much bigger problems than the authorship of the books of Moses.

Deuteronomy

These be the words which Moses spake unto all Israel on this side Jordan in the wilderness, in the plain over against the Red sea, between Paran, and Tophel, and Laban, and Hazeroth, and Dizahab.

— Deuteronomy 1:1

One of the Hebrew names for the book of Deuteronomy is Sepher Devarim, from the first line of the book, which begins, “These are the words.” The word sepher means “book” and devarim means “words.” Its Hebrew title is therefore “Book of Words.” Many Hebrew book titles are based on the first line of the document. However the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, The Septuagint, calls this book Deuteronomion, for “Second Law.” When Jerome wrote the Vulgate, the Latin translation of the Bible, he kept the Greek name, and that’s where we get our name for this fifth book of the Torah.

Deuteronomy is often considered a review of the Law found in Exodus and Leviticus. This is correct in a sense because Moses takes Deuteronomy to review all that God asked of them and to make a sermon out of it. More importantly, these are the words of Moses, words that Moses spoke to the people as his last full instructions before their move into the Promised Land.

Moses

Before we go any farther, we need to talk about Moses. There’s an old saying that, “familiarity breeds contempt.” We are in danger of presumption when we read the Torah, because we are familiar with Moses, and we might not appreciate his significance. We need to put Moses in perspective.

He was the founder of Israel’s religion, if I can express it that way. He was the mediator of the Covenant (which Moses explains in Deuteronomy 5:2–5). He is identified in Deuteronomy 34:10 as Israel’s first prophet. Few Christians appreciate that the Torah is filled with prophecy.

God called Abraham a prophet in Genesis 20:7, but Israel didn’t yet exist as a nation. I can, therefore, argue that Moses was the first prophet to the nation. Through Moses, God set such a high standard that all subsequent prophets (until Christ of course) lived in the shadow of Moses. Moses was unquestionably the most venerated of the prophets, and the New Testament writers quote Moses more than anybody else.

Moses did not merely have visions or dreams, as other prophets. God spoke to him face to face. This is a big deal. When Miriam and Aaron challenge Moses, insisting that they are prophets too, God rebukes them for their arrogance, saying:

And the Lord came down in the pillar of the cloud, and stood in the door of the tabernacle, and called Aaron and Miriam: and they both came forth.

And he said, Hear now my words: If there be a prophet among you, I the Lord will make myself known unto him in a vision, and will speak unto him in a dream.

My servant Moses is not so, who is faithful in all mine house.

With him will I speak mouth to mouth, even apparently, and not in dark speeches; and the similitude of the Lord shall he behold: wherefore then were ye not afraid to speak against my servant Moses?

And the anger of the Lord was kindled against them; and he departed.

— Numbers 12:5–9

This is not a small thing. Jesus even spoke to His disciples in parables, but God spoke to Moses directly, as man speaks to his friend. Exodus 34:34–35 tell us Moses would wear a vail because the presence of God made his face glow. We should, therefore, take great care to recognize the words of God through Moses.

The death of Moses is an interesting issue. Jude 1:9 tells us that Michael the archangel fought with Satan over the body of Moses. Why? Nobody on earth knows besides the Holy Spirit. Moses and Elijah (who never died) show up at the Transfiguration in Matthew 17. I suspect that these are the Two Witnesses of Revelation 11, partly because the Two Witnesses have abilities that match miracles that were accomplished through Elijah and Moses.[8] It is possible that Moses’ ministry on earth is not finished.

Deuteronomy One

Deuteronomy is essentially a series of sermons. It’s interesting that Moses’ words are addressed to all of Israel. The expression “all Israel” occurs at least twelve times in the book.[9]

These be the words which Moses spake unto all Israel on this side Jordan in the wilderness, in the plain over against the Red sea, between Paran, and Tophel, and Laban, and Hazeroth, and Dizahab.

(There are eleven days’ journey from Horeb by the way of mount Seir unto Kadeshbarnea.)

— Deuteronomy 1:1–2

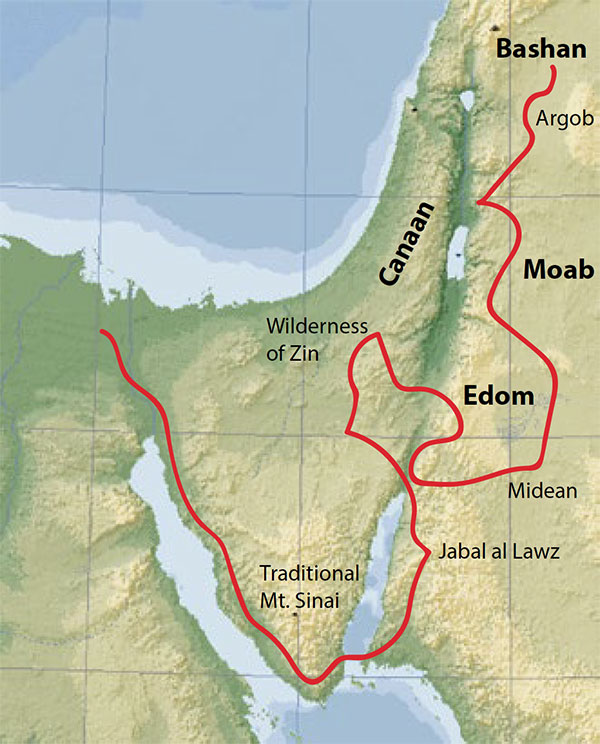

This is a rough map that shows the path to Jabal al-Lawz in Saudi Arabia. Many Bibles presume that the Israelite wanderings remained in the Sinai Peninsula. There is a problem with that; there’s absolutely no evidence for it. Hundreds of years of archeological research has revealed no trace of evidence on the Sinai Peninsula. The great discovery of recent years is Jabal al-Lawz, the mountain I believe is the real Mount Sinai. Just as Paul said in Galatians 4:25, Mount Sinai is in Arabia, not the so-called Sinai Peninsula.

There are all kinds of evidence in support of the Jabal al-Lawz site, not the least of which is that the mountain there has been melted from the outside in. The top third of the mountain is black. Those who have gone up there and broken the granite report that it has been heated intensely on the outside.[10] There are also pictographs and altars in that area.

From Jabal al-Lawz the Israelites traveled up through the Wilderness of Sin (think Sinai), wandered back to Ezion-geber, and then finally headed back up through Edom, Moab, and Bashan before eventually crossing over the River Jordan to attack Jericho under Joshua.

Here in Deuteronomy, Moses is going to review their wilderness history. I want to acquaint you with the general zones the Israelites traveled through. Notice that Edom is east of the Jordan, well south of the Dead Sea. Edom is just north of Midian, where Moses spent forty years herding sheep before God called on him to lead the Exodus. The Israelites ended up back in that area during their wanderings. North of Edom is Moab, where Balak the king of Moab tried to have the prophet Balaam curse Israel, only to find the LORD would only allow Balaam to bless Israel. North of all that is Bashan, which we associate with the Golan Heights. There God led the Israelites to kill certain giants before entering the Promised Land. Remember Og of Bashan, whose iron bedstead was 9 cubits (13.5 feet) long?[11] These years of traveling and these early fighting victories are in their past. Here in Deuteronomy, Moses speaks to the children of Israel and gives them their final instructions from the LORD through him.

And it came to pass in the fortieth year, in the eleventh month, on the first day of the month, that Moses spake unto the children of Israel, according unto all that the Lord had given him in commandment unto them;

— Deuteronomy 1:3

The LORD

In the Old Testament, God is addressed by a name spelled with four letters: יהוה — YHWH. The Jews reverenced the name so greatly, they stopped speaking it. Instead of reading God’s name out loud, they substituted the word Adonai, which means “Lord.” For this reason, its correct pronunciation has been lost. Most Bibles replace those letters with the traditional term “LORD” (capitalized). Many of us are familiar with the old German pronunciation “Jehovah” but J and V are sounds not found in the original Hebrew, and “Yahweh” is closer to being correct.

The Hebrew name for God, YHWH, is of God’s own choosing, and it is the name that emphasizes God’s personal covenant relationship with the nation of Israel. It means, “I am” in the sense of perpetual existence, and it is the name God gave to Moses at the burning bush:

And Moses said unto God, Behold, when I come unto the children of Israel, and shall say unto them, The God of your fathers hath sent me unto you; and they shall say to me, What is his name? what shall I say unto them?

And God said unto Moses, I Am That I Am: and he said, Thus shalt thou say unto the children of Israel, I Am hath sent me unto you.

— Exodus 3:13–14

We find in Jewish communities today, the Jews won’t even spell out the word “God.” Instead, they’ll write “G-D” out of respect. The Jews are diligent in their efforts to venerate the name of God. As Christians, we enjoy God’s revelation of Himself through Jesus Christ. This is one of the benefits we enjoy. Furthermore, those of us who are in Jesus Christ know God as our Father.

Jesus told His disciples to address God as “our Father” when He taught them to pray in Matthew 6,[12] and we learn that the Spirit of God leads us in our spirits to call God, “Daddy.”[13] The idea of God as our Father is an infrequent designation in the Old Testament, but it becomes pervasive in the New Testament because we have that relationship through Christ. Jesus always calls God “Father” except once, and that’s when He’s hanging on the cross as punishment for our sins. In Matthew 27:46, He echoes Psalm 22:1, crying out, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” Jesus couldn’t address Him as “Father” there, because He was in our shoes. Christ Jesus took our place as condemned sinners, and He allowed us to take His place and become God’s sons and daughters.

The concept of God as our Father was not familiar to the Israelites, however. To them, He was the I AM, who led them out of Egypt with great signs and wonders and miracles. He was I AM who provided for them 40 years in the desert. As Deuteronomy begins, Moses is going to give the Israelites a sermon, and his authority comes from the fact that he is speaking to them on behalf of the I AM.

The Setting

After he had slain Sihon the king of the Amorites, which dwelt in Heshbon, and Og the king of Bashan, which dwelt at Astaroth in Edrei:

— Deuteronomy 1:4

The Israelites have had victories in defeating the giant kings who live in the land west of the Jordan River. Sihon and Og were huge men ruling over the are now known as the Golan Heights. Bashan was a lush, well-watered area, and the Amorites dominated it until God brought the Israelites against these leaders. They are now in a staging area to go in and take the land that God promised them 40 years earlier.

On this side Jordan, in the land of Moab, began Moses to declare this law, saying,

— Deuteronomy 1:5

He’s going to refer to the first attempt to enter the Promised Land years earlier, and that’s the primary subject of the rest of this chapter. The word here “to declare” is באר — ba’ar — which means “to make plain” or “to expound.” After this five-verse introduction, Moses begins to speak and expound on the Law. In its most literal sense, the word ba’ar means “to dig” as in “to dig a well.” When it’s used in the sense “to declare,” it is generally paired with adverbs like “very clearly.” Moses is not simply declaring the Law, as though he’s reading it and saying, “Okay this is what it says.” No, Moses is going to explain the real demands of it. The town of Beersheba is actually Ba’ar Sheba which means “well of an oath.” We think of an expositional Bible study that way. We go beyond what the Bible simply says, and we expound on what it really means. We dig into it. That’s what Moses is going to do here.

In Galatians 3:24–25, Paul refers to the law as our schoolmaster. The Law is there to instruct us, and Romans 5–6 shock us by telling us that one purpose of the Law is not for us to sin no more. If you think I’m kidding, read those two chapters. The purpose of the Law is actually to reveal our sin so that we can understand that our position is inescapable. Romans 3 already warned us this was coming:

Therefore by the deeds of the law there shall no flesh be justified in his sight: for by the law is the knowledge of sin.

— Romans 3:20

By the Law is the knowledge of sin. The Law is there so we can understand where we stand. I hope that bothers you a little. On the other hand, it’s a relief to know that the purpose of the Law is to drive toward God for forgiveness, and not away from Him because we’ve failed. If you carefully read Romans 5 and 6, you’ll find there that Law is a very critical topic.

This generation that Moses is talking to is a more faithful generation than its parents. This is the end of the 40 years in the Wilderness. The old guard has been wiped out. Those who didn’t have the guts to cross over into the land flowing with milk and honey back in Numbers 13:25–14:38 are gone. They have had 38 years of distance between the events of the Exodus and the items on their horizon right now. It’s the new generation that’s afoot, and Moses has a burden here to teach them. These are the ones that will carry the purposes of God into the new land under Joshua.

Of course, most people see the Torah as a list of rules, but that’s not so. It contains laws, but the Torah is much more than that. It’s direction for us. It is instruction, and that is the key thing. As we finish this introduction, let’s look at the first words of Moses’ speech:

The Lord our God spake unto us in Horeb, saying, Ye have dwelt long enough in this mount:

Turn you, and take your journey, and go to the mount of the Amorites, and unto all the places nigh thereunto, in the plain, in the hills, and in the vale, and in the south, and by the sea side, to the land of the Canaanites, and unto Lebanon, unto the great river, the river Euphrates.

Behold, I have set the land before you: go in and possess the land which the Lord sware unto your fathers, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, to give unto them and to their seed after them.

— Deuteronomy 1:6–8

These words set the tone for the entire sermon. Right from the beginning, we find an absolutely unique, inviolable relationship between the Creator of the Universe and this peculiar people. God is going to bring the people of Israel into the Land He swore to their forefathers. It’s an incredible moment in Israel’s history. They will face challenges, but God will give them victory after victory. In the book of Deuteronomy the words “the Lord our God” occurs almost 50 times, and Yahweh is sovereign over Israel’s history.

The world is still challenging Israel’s right to that Land today. There are big world powers all meddling in the Middle East. Most of these are oblivious to the fact that they’re poking a finger in the eye of God. Britain failed to deliver the land allocated for Israel to the League of Nations by peeling off 75% and declaring it the state of Jordan. There’s your Palestinian state. The world is Satan’s domain, and the world is anti-Semitic. Yet, God has always had purposes for Israel that He will fulfill. He brought the Israelites into the Land in the days of Joshua, and He’s got His hand on the Land of Israel today.

… To be continued. Part 2 will appear in the Sep. 2017 issue of the Personal Update.

This excerpt was adapted from Dr. Chuck Missler’s Expositional Commentary on the Book of Deuteronomy, available from the K-House Store.

Notes:

- Astruc, Jean (1753), Conjectures sur les Mémoires Originaux, Dont Il Paraît que Moïse S’est Servi Pour Composer le Livre de la Genèse. ↩

- Kitchen, K. (1966), Ancient Orient and Old Testament (p. 23). London: Tyndale. ↩

- 1 Kings 6:1 ↩

- Exodus 24:4; Numbers 33:2; Deuteronomy 31:9, 24–26; Joshua 8:31–32, 23:6; 1 Kings 2:3, 8:9; 2 Kings 14:6; 2 Chronicles 23:18, 25:4, 30:16, 33:8, 34:14; Ezra 3:2; Nehemiah 8:1, 14, 13:1; Daniel 9:13; Malachi 4:4 ↩

- Exodus 33:11; Numbers 12:6–8; Deuteronomy 34:10 ↩

- Exodus 17:14 ↩

- Exodus 24:13, 33:11; Numbers 27:18; Deuteronomy 31:14, 32; 34:9 ↩

- Revelation 11:6; Exodus 7:20; 1 Kings 17:1, 18:1, 18:41–45 ↩

- Deuteronomy 1:1, 5:1, 13:11, 21:21, 27:9, 29:2, 31:1, 7, 11, 30, 32:45, 34:12 ↩

- Cornuke, B. The Mountain of God. ↩

- Numbers 21:33–35 ; Deuteronomy 3:11 ↩

- Matthew 6:7–9 ↩

- Romans 8:15; Galatians 4:6 ↩