Competition over energy resources is not a recent development. Almost as soon as oil was discovered, it became a contested commodity.

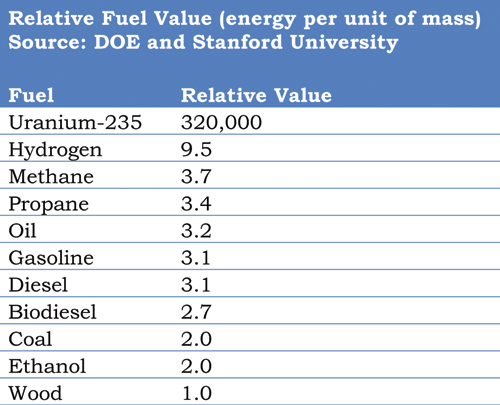

Man’s history has been marked by the energy we use. In early times, man used wood as a fuel for fire, the heat of which could provide warmth, cook a meal, or forge an iron blade. As wood became scarce, man turned to fossil fuels, mainly coal, to power the industrial revolution. Oil and natural gas eventually replaced coal as a primary industrial and personal fuel because they were easily distributed and highly effective as energy sources.

Energy is needed to grow an economy and the world is demanding ever-increasing amounts of it. While many of the industrialized countries, known as OECD,1 are working to develop alternative energy sources (e.g. New Zealand’s geothermal resources), the world’s economy will continue to rely on hydrocarbon-based energy sources for at least the next 20 years.

The “Great War”

Competition over energy resources is not a recent development. Almost as soon as oil was discovered, it became a contested commodity. At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, one of the first troop deployments by the British Empire was the Dorsetshire regiment to Basra, Iraq, where it was quickly joined by 51 other British divisions.

This would seem to be a strange deployment for the start of the war, but one must realize that both the British and German Navies were switching from coal to oil to fuel their ships and a stable source of supply was critical.

Neither Germany nor Great Britain had much in the way of oil reserves, but the Germans were already anticipating filling their energy needs. Prior to the start of World War I, the Germans were constructing the Berlin-Baghdad railway (part of which is now known as the Orient Express), which ran near Baghdad and the Mosul oil fields. The British landing at Basra secured Iraq’s newly developed oil supplies and kept it out of German hands.

On May 16, 1916 the British and French concluded a secret bargain that came to be known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement. While it is more commonly known as an agreement that raised Jewish hopes for a homeland, its larger purpose was to divide up the Ottoman Empire, and its oil reserves in Mesopotamia (now Iraq), in the event that the allied powers won the war.

As Sir Maurice Hankey, the secretary of the British War Cabinet wrote, “…oil in the next war will occupy the place of coal in the present war…therefore, control over these oil supplies becomes a first-class British war aim.”

It was this thirst for oil that thrust the Middle East center stage in geopolitics.

World War II – A War Over Resources

In 1923, former Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt wrote an article for Asia Magazine entitled “Shall We Trust Japan?” In the article Roosevelt observed that “long before the events of 1914 centered attention elsewhere, an American-Japanese war was the best bet of prophets. Its imminence began to be taken for granted.”2 Roosevelt’s concern was justified, for while in the 1930s Adolf Hitler was searching for lebensraum “living space” in Europe, Japan was extending its tentacles into mainland China and the countries of the South China Sea.

Nations like Japan and Germany had to import resources like oil and rubber from nations which were outside their sphere of influence, who were often hostile towards them at best. To secure a supply of materials to fuel their economies, Japan and Germany decided to physically gain control of them through conquest.

While the United States could not do much to restrict German expansionism on the European Continent, it did have options available to stop the Japanese.

With American politics turning against Japan as reports of the Rape of Nanking started to reach its shores, the U.S., Britain, and the Netherlands East Indies initiated an oil embargo against Japan in August 1941.

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a direct result of the embargo the United States placed on Japan. It sought to neutralize American power in the Pacific and seize oil, metal and food assets in South Asia.

The Seven Sisters

The end of World War II brought an economic boom to the United States. America became the engine that drove the post-war recovery. The engine had to be fueled—and the fuel of choice was oil. Oil started to become a strategic material in the postwar world and almost every country began a campaign to secure their supplies.

The most successful group in this contest was a cartel of American, British, and Dutch companies that were nicknamed the “Seven Sisters.” The Sisters included Exxon, Mobil, Chevron, Texaco, Gulf, Royal Dutch/Shell, and British Petroleum, which held interests in oil fields throughout the Middle East. Oil and the Middle East were now inexorably tied.

Ezekiel Fulfilled

On May 14, 1948, the United States became the first country to recognize the State of Israel, just 45 minutes after David Ben Gurion, citing Ezekiel as his authority, proclaimed Israel an independent nation. President Harry Truman recognized the fledgling state in the face of stiff opposition in his own State Department, who were concerned that he was jeopardizing U.S. oil interests in the Middle East by doing so.

Truman was able to recognize Israel with little fear of Arab retaliation due to the preeminent place the United States held in the postwar world. However, by the latter half of the 1960s, its will to exert global power was sapped by an unpopular war and internal political strife. At the same time, Anti-Americanism had taken hold throughout much of the world. America had lost its grip on oil supplies.

By 1970, two-thirds of the increase in post-war oil consumption was being satisfied by relatively few oil producing countries. These countries suddenly found themselves with their hands on the world’s oil spigots and they would soon start closing those valves.

In 1969, oil began to be used as a weapon with the creation of an oil cartel called OPEC.3 OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) is a cartel of twelve countries founded in 1960 whose purpose is to coordinate the policies of the oil-producing countries. While having its beginning as an economic cartel, OPEC remade itself as a political entity, mainly in response to U.S. foreign policy. In October 1973, OPEC declared an oil embargo in response to the United States’ and Western Europe’s support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War of 1973. The result was a rise in oil prices from $3 per barrel to $12 and the start of gas rationing.

The Gulf Wars

A period of relative oil stability maintained during the 1980s exploded in 1990 when Iraq accused Kuwait of stealing its oil and invaded the country, a move that was largely seen as an attempt to gain control of Kuwait’s large oil reserves. It also served to curb Kuwaiti oil production, raise oil prices, and repay the massive debt it amassed while funding its 10-year war with Iran.

Iraq’s advance into Kuwait also terrified Saudi Arabia’s royal family. The House of Saud feared that once Iraq acquired Kuwait’s oil, they would move against Saudi Arabia’s fields and control nearly 50% of the world’s oil reserves. This was a situation the West could not tolerate. A coalition of forces consisting of the NATO allies and the Middle Eastern countries of Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Egypt assembled in Saudi Arabia and launched an attack on the Iraqi Army to push them out of Kuwait and back into Iraq. The forces launched an air campaign against Iraq code-named “Desert Shield,” followed by a 100-hour land war, named “Desert Storm,” which drove Iraqi forces from Kuwait.

The “First Gulf War” had several unintended consequences. First, Hussein tried to break the coalition by launching Scud missile attacks into Israel, hoping to put the conflict into a religious context rather than an economic one. The second consequence of the war was that the presence of foreign troops in one of Islam’s holiest regions inflamed the jihadists in the region. This disgust at infidels in Saudi Arabia translated into jihad.

The First Gulf War set off a series of terrorist attacks that took over 3,000 lives, culminating in the 9-11 attacks in 2001, which killed an additional 3,000 people. The 9-11 attacks touched off what has been called the “War on Terror,” which, many times, masked economic and resource motives instead of ideological ones.

One of the offshoots of this new kind of enemy—terror—led to the Second Gulf War. While part of the Bush administration’s rationale for the war was to remove a base for terrorism, even George Bush admitted oil entered into the equation:

If Zarqawi and [Osama] bin Laden gain control of Iraq, they would create a new training ground for future terrorist attacks. They’d seize oil fields to fund their ambitions.4

There are other places besides the Middle East where oil has been a major factor in territorial conflicts. The ongoing disputes between China and Japan over eight uninhabited islands in the South China Sea called the Senkaku islands, and China with Vietnam over three square miles of land of the Spratly islands, is largely over oil.

China’s claims to these islands are based on maps drawn out centuries ago when the Chinese empire laid claim to most of the South China Sea. Why are they pressing these claims now? The answer is that the estimated oil reserves in the South China Sea stand at 213 billion barrels, an amount that would exceed the proven reserves of every country in the world except Venezuela!

Even the conflict over the far-off Falkland Islands isn’t over sovereignty as much as oil reserves. Edison Investment Research predicts the waters off the islands may hold in excess of 4.7 billion barrels of oil. By comparison, the biggest discovery in the British North Sea of the past 11 years is believed to hold only 300 million barrels.

Israel – An Energy Superpower?

Even Israel is transforming itself into a land awash with oil and gas. When the nation’s offshore Tamar field came online and began delivering natural gas direct to Haifa in March 2013, it signaled the end of Israeli dependence on its Arab neighbors for its gas imports. It also signaled the beginning of Israel’s rise to energy superpower status.

While Tamar marks Israel’s entry into the world’s energy stage, the enormous Leviathan gas field completely overshadows it. By 2018, Leviathan is estimated to have twice the proven gas reserves of Tamar. These two fields also hold out the tantalizing prospect of significant amounts of oil being discovered there as well.

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin realizes the importance of this discovery and is very concerned. The Israeli find, together with the shale gas revolution in the United States means that Russia’s lock on the European Gas supplies (and its political leverage) may be coming to an end. Putin is putting on a full-court press on Israel to try to persuade them to give Russia a major stake in the future distribution of Israel’s gas resources.

But what happens if Israel rebuffs these and other overtures to produce and distribute its resources?

Ezekiel 38 talks about the spoils that Gog and Magog will try to take from the Middle East. As Israel becomes an energy superpower in its own right, may the hydrocarbon deposits under the land and the sea prove to be a spoil that is irresistible to other energy-hungry countries? It is a scenario that those who are monitoring the “signs of the times” need to watch.

Notes:

- Organization of Economic Co-Operation and Development.

- Mallon, P. (1940, October 3). News Behind the News. The Brownsville Herald, p. 4.

- Algeria, Angola, Ecuador, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Venezuela.

- Loven, Jennifer, (2005, August 31). Bush gives new reason for Iraq war. Boston.com.

Sources

- Dahl, E. J. (Winter, 2000). Naval innovation: from coal to oil. Joint Force Quarterly, 113-115.

- Engdahl, F. W. (2012). A Century of War: Anglo-American Oil Politics and the New World Order. Progressive Press.

- Greenspan, A. (2008). The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World. New York: Penguin Books.

- Sampson, A. (1976). Seven Sisters: Great Oil Companies and the World They Made. Bantam Books.

- Yergin, D. (2011). The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power. New York: Free Press. Kindle Edition.