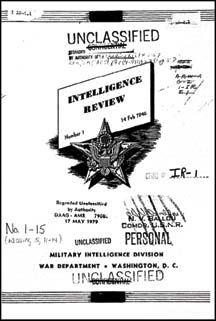

From the War Department (now the Department of Defense) archives comes a 63-year-old military intelligence review, entitled “Islam: a Threat to World Stability,” that inadvertently provides incredible insight into the challenges faced by Christians in today’s world.

Written in a no-holds-barred politically incorrect language not commonly found today, the author establishes a clear and compelling picture of the “Moslem”1 world of 1946, which elucidates many of the words and concepts today whose meanings may seem blurred or lost in antiquity.

The intelligence estimate is transposed verbatim in Parts 1 and 2 of this series. Our Issachar Database (IDB) Folio Manager for Islam (and Military Technology), Ray Sarlin, will then update the intelligence estimate with the corresponding facts and figures for today in Part 3.

The entire issue of Intelligence Review No. 1 of 14 February 1946, published in the immediate aftermath of World War II less than a month before the term “Iron Curtain” was first used by Winston Churchill, is available in the Issachar Database.

The entire issue of Intelligence Review No. 1 of 14 February 1946, published in the immediate aftermath of World War II less than a month before the term “Iron Curtain” was first used by Winston Churchill, is available in the Issachar Database.

It examines the state of a world where the one-month-old United Nations Organization promised the hope of peace; the Chinese Nationalist-Communist Civil War was resuming and open hostilities would continue for three long years; the CIA was two weeks old; and, the bikini, Tupperware and ENIAC (“Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer”), the first general-purpose computer, were unleashed on the world. The Middle East would see the United Kingdom grant Transjordan independence on March 22, even as they continued to withhold a “Jewish National Home”; the year would later see a bombing campaign by Jewish terrorists. France would also grant Syria its independence on April 17. Continuing violence between Muslims and Hindus in India left thousands dead.

The building blocks for events in our lifetimes were tumbling into place...

Islam: A Threat to World Stability

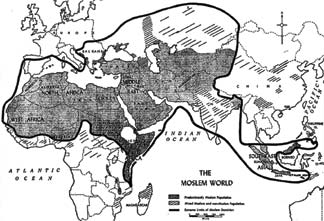

The Muslim world sprawls round half the earth, from the Pacific across, Asia and Africa to the Atlantic, along one of the greatest of trade routes; in its center is an area extremely rich in oil; over it will run some of the most strategically important air routes [see chart, below].

With few exceptions, the states which it includes are marked by poverty, ignorance and stagnation. It is full of discontent and frustration, yet alive with consciousness of its inferiority and determined to achieve some kind of general betterment.

With few exceptions, the states which it includes are marked by poverty, ignorance and stagnation. It is full of discontent and frustration, yet alive with consciousness of its inferiority and determined to achieve some kind of general betterment.

Two basic urges meet head on in this area, and conflict is inherent in this collision of interests. These urges reveal themselves in daily news accounts of killing and terrorism, of pressure groups in opposition, and of raw nationalism and naked expansionism masquerading as diplomatic maneuvers. The urges tie together the tangled threads of power politics, which—snarled in the lap of the United Nations Assembly—lead back to the centers of Islamic pressure and to the capitals of the world’s biggest nations.

The first of these urges originates within the Muslims’ own sphere. The Muslims remember the power with which once they not only ruled their own domains but also overpowered half of Europe, yet they are painfully aware of their present economic, cultural, and military impoverishment. Thus a terrific internal pressure is building up in their collective thinking. The Muslims intend, by any means possible, to regain political independence and to reap the profits of their own resources, which in recent times and up to the present have been surrendered to the exploitation of foreigners who could provide capital investments. The area, in short, has an inferiority complex, and its activities are thus as unpredictable as those of any individual so motivated.

The other fundamental urge originates externally. The world’s great and near-great powers covet the economic riches of the Muslim area and are also mindful of the strategic locations of some of the domains. Their actions are also difficult to predict, because each of these powers sees itself in the position of the customer who wants to do his shopping in a hurry because he happens to know the store is going to be robbed.

In an atmosphere so sated with the inflammable gases of distrust and ambition, the slightest spark could lead to an explosion which might implicate every country committed to the maintenance of world peace through the United Nations Organization. An understanding of the Muslim world and of the stresses and forces operative within it is thus an essential part of the basic intelligence framework.

History of the Muslims

The influence which integrates the Muslims1 is their religion, Islam.2 This religion began officially in the year 622 A.D., when Mahomet3 was driven from Mecca because of his preaching of a synthesis of Jewish and Christian heresy, and took fiight to Yathrib (Al Medinah).4 Taking advantage of the age-old feud between the two towns, he soon rallied an army to his side, made extensive compromises with Medinah paganism, and attacked Mecca. At his death in 632 A.D. he was the master of all Arabia.

His successors, the Caliphs (or Khalifs) quickly overran much of the known world; they reached India and penetrated Trans Caspiana and Musa ibn Tariq, and crossed the straits at the western end of the Mediterranean, giving to the mountainous rock at their entrance the name of Jebel Al Tariq (the mountain of Tariq), which the Spaniards later corrupted to “Gibraltar.”

In 732 A.D.—just one century after the death of the Prophet—the Muslim advance in western Europe was finally turned back at Tours, France, by Charles Martel. To the north of Arabia, the Byzantine Kingdom held back the Muslim tide until the 15th century, when Constantinople fell and central Europe became a Turkish province. From that high point, Muslim expansion gradually receded. Although for centuries the Muslim world had been contributing to western arts, science, and trade, a period of increasing sterility set in, and during the next 400 years the Muslims advanced very little in any phase of human endeavour.

At the present time there are no strong Muslim states. The leadership of the Muslim world remains in the Middle East, particularly in Arabia. This area lies near the geographical center of Eurasia’s population, with industrial Europe to the west and the agricultural countries of India, Indonesia, and China to the east. Through it passes the Suez Canal; and north of it lie fabulously rich oil fields around the Persian Gulf.

Present Forces Tending to Weaken Muslim Unity

The many forces tending to tear the Muslim world apart have been so strong that there has been no central Muslim authority since the 8th century; the factors which generate disunity are discussed briefly below.

1. Lack of a common language: Muslims east and south of the Tigris River (except those in Malaya and Indonesia) usually speak Urdu, Persian, or Turkish. West of the Tigris River, the dominant language is Arabic, but its far western dialects are unintelligible to the eastern Arab.

2. Religious schisms: The oldest of these schisms is the Sunni-Shiah controversy, which arose in the 8th century. The eastern Caliphate, with its capital at Baghdad, gave impetus to the Shiah sect, but it was not until the 17th century that the Shiah creed was officially adopted in Iran. The majority of Muslims, however, belong to the Sunni (unorthodox) sect, although islands of Shiah believers exist in Sunni regions. Neither sect has a recognized leader. In theory the Sunni should have a Caliph, a successor to the Prophet, but the historic Caliphate came to an end in Baghdad about 1350, and there have since been only “captive” Caliphs—puppets set up by secular powers and not generally recognized. The Emir Husayn of’ Mecca desired the British to recognize him as Caliph in 1916, and in recent years King Faruq (Farouk) of Egypt has made gestures indicating he would be willing to play the part. Nationalism keeps the Muslims apart, however, and no serious bid for the traditional role of a leader of Islam now exists. Islam is also beset with modern movements which try to make it conform to new historical evidence and to modern psychology and science. These have included a reform movement known as Babism, which appeared a century ago in Iran, followed by Bahaism, which adopted many features of the former.

Along with “the acids of modernity,” there have been atavistic movements designed to preserve the original “purity of Islam.” In 1703 an Arab chieftain, Abdul Wahab, revived a fanatically purist faith, which soon swept over all Arabia. Thousands of “pagan Muslims” were massacred at Mecca by desert adherents of the new faith. Around 1850 the movement suffered an eclipse but again appeared in 1903, led by Abdul Aziz of the Saud family. Again it overran the Arabian Peninsula, and it is now the recognized faith of Saudi Arabia. These Wahabis believe that the Koran is the only source of faith and that it contains the only precepts for war, commerce, and politics; they regard any innovation as heresy.

Paralleling this reactionary tendency, there have appeared in Egypt and elsewhere several societies that stress Islamic culture; these are openly anti-European and secretly anti-Christian and anti-Jewish. The best-known is the Ikhwan el Muslimin (Brotherhood of Muslims), which encourages youth movements and maintains commando units and secret caches of arms (it is reported to have 60,000 to 70,000 rifles). The militant societies, such as the Shabab Muhammad (Youth of Mahomet) and the Misr Al Fattat (Young Egypt), are led by demagogues and political opportunists. They issue clandestine pamphlets, attack the government, stir up hatred of the British, and sow the seeds of violence.

In recent months, Premier Ahmad Maher of Egypt was assassinated, and former Premier Nahas Pasha was wounded by people associated with these groups. Christian minorities in the Middle East fear these fanatical and nationalistic Muslim societies which exploit the ignorance and poverty of the masses, and even the more enlightened Muslim leaders must cater to their fanaticism in order to retain their positions.

3. Geographical isolation: The Indian Muslim knows little or nothing of his fellow believers in Mongolia and Morocco. To a Sudanese, Turkey and Iran are meaningless terms. High mountains, broad deserts, and great distances separate one group from another, and provincialism has inevitably resulted.

4. Economic disparities: Throughout the Muslim world, social conditions closely approximate Medieval feudalism. In Egypt, a few thousand people own the land on which 13 million labor as share croppers. In Saudi Arabia, where the purest desert “democracy” exists, the contrast between the living conditions of the peasant and the feudal land-holding classes is very great. That contrast is common throughout the whole Muslim world, where the lack of industrial development has made it easier than elsewhere to retain the feudal system of exploiting the land and the peasants.

Social reform has been given only lip service, and the Muslim peasants have a growing conviction, stimulated by Soviet propaganda, that the landowners are their worst enemy. In northern Iran, the peasants have openly revolted under the instigation and protection of the Red Army, and such a revolt can happen anywhere in the Muslim world....

In Part 2 of this three-part series, “Islam: a Threat to World Stability,” we will continue to examine forces in 1946 tending to weaken Muslim unity, then examine those tending to strengthen it, reaching a very interesting and relevant conclusion.

Notes:

- Moslem was the preferred spelling until the first half of the 20th century. Today, Muslim is the preferred spelling.