The Bible is remarkable in its ability to reach the tenderest parts of our hearts and the roughest corners of our minds. Many of us have a favorite book of the Bible; Genesis, Isaiah, Romans, Revelation — each is powerful and touches us in deep, personal ways. When somebody once asked me to name my favorite book of the Bible, I realized the Book of Ruth might easily top the list.

That might seem surprising. Ruth is a small interlude between Judges and 1 Samuel in our English versions, one that tells the simple story of King David’s great grandmother. Yet, we find a wonderfully elegant love story in its four short chapters. Ruth holds a great treasure; as a work of literature, Ruth is venerated even in secular college classrooms, but, more importantly, we find the Gospel threaded throughout the entire tale. In fact, it’s one of the most dramatic books of prophecy in the Bible, and I regard this book as an essential prerequisite to studying the book of Revelation.

In Ruth, we find that every detail carries not just a story of romance, but specifically the Romance of Redemption. It gives us a perspective of God’s plan for us, and you and I are profiled here in a very surprising way. In Ruth, we discover a concept called the Goel — the Kinsman-Redeemer.

We also find here a primer on the distinctions between Israel and the Church. One of the tragic by-products of Christianity today is confusion about God’s purposes for Israel. God has a specific plan for Israel and a specific plan for the Church, and in certain ways these are mutually exclusive. They are parallel but separate, and as we read Ruth, we want to remain sensitive to the differences.

The Bible is a masterpiece of communication from a God outside our time domain. The message of salvation is simple enough for the youngest of minds and yet, intellectuals can spend decades studying its pages and still find new hidden treasures in each passage. As we read Ruth, we need to adjust ourselves to multiple levels of understanding.

Prophecy as Pattern

I have also spoken by the prophets, and I have multiplied visions, and used similitudes, by the ministry of the prophets.

— Hosea 12:10

In our culture, we tend to think of prophecy as a prediction with a future fulfillment. That’s what we think of as prophecy. That’s the Greek mindset, however. The Hebrew model is a little different. Hebrew prophecies about the future are based on patterns. As we study the Hebrew literature, we continually see patterns of the Messiah profiled in Israel.

In Genesis 22, the Akedah, Abraham binds Isaac for sacrifice, but a ram is sent to take the place of the young man. It’s clear that Abraham knows he’s acting out prophecy. In verse 14, Abraham names the place Jehovah Jireh — “the LORD will see to it” — or as it was called continually afterward, “In the mount of the LORD it shall be seen.” Two thousand years later, on that very spot, another Father did offer His Son. Hebrews tells us that Abraham believed God could raise Isaac from the dead, and in his willingness to trust God and sacrifice Isaac, Abraham acted out the pattern of a prophecy to be fulfilled in the Son of God Himself.

The Book of Ruth certainly has a historical application. The story describes a series of events that actually took place during the times of the Judges. We need to understand the historical period during which these events took place.

There’s also a homiletic application in this study. We can take the lessons we learn in Ruth and apply them to our own lives.

We will also discover that Ruth has some prophetic applications. There are mystical revelations that might surprise us if we missed them at first glance. In Hebrew hermeneutics, the rabbis have what they call the remez — the hint of something deeper. We run across what appear to be small rabbit holes, but they open the door to another world of perspective.

We find in this story that each of the principal characters represents a character in the greater story of God’s love for us. Naomi is Israel, the people of the Pleasant Land, the apple of God’s eye. Ruth is the Gentile Believer, the Church, cast out by the Law but brought in by God’s grace. Most importantly, Boaz represents Jesus Christ, our Kinsman-Redeemer. He is the husband of the Church, to the blessing of Israel.

These four chapters provide one of the most phenomenal patterns in the Bible. There are critical links in the chain. Like Bethlehem. Why is Bethlehem relevant? Our Christmas cards remind us every year that Bethlehem is associated with the house of David, but why? The throne of David is an important topic. The cross, of course, is the pivotal event in the entire universe. The crown that Jesus is destined to wear also takes a central position in the picture here. We learn about the role of the Kinsman-Redeemer. We also find important clues about the distinction between the Church and Israel, and we want to be sensitive to those issues. Strangely enough, this Old Testament book is the most relevant book for the Church. That sounds like a contradiction, but it’s interesting that even the Jewish community always reads Ruth at the time of Shavuot — Pentecost.

The Heptadic Calendar

More than a century ago, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch said, “The Jews’ catechism is his calendar.” I find his statement very interesting. If we are going to understand the Bible, we need to have a feeling for the Jewish calendar. The feasts of Israel are a yearly reminder of God’s purposes and plans, put in place to teach prophetic events in advance.

In the spring, there are three feasts of Israel which represent Christ’s First Coming. In the fall, there are three more feasts that represent Christ’s Second Coming. In the middle is Shavuot, the Feast of Weeks. The story of Ruth takes place during the barley and wheat harvests, in the early and late spring, centering on the time of Shavuot.

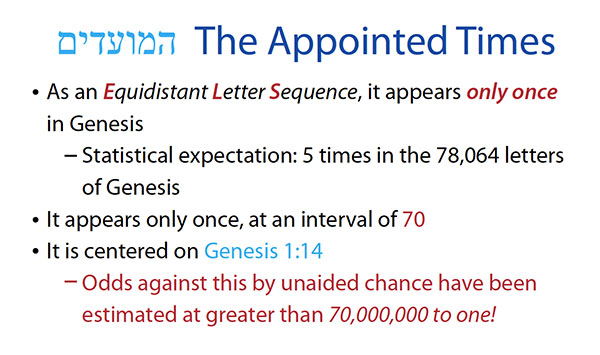

Genesis 1:14 says, “And God said, Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days, and years.”

The word translated “seasons” here is HaMoyadim, which means “the appointed times.” The lights in the firmament set signs for highlighting the appointed times. There are 70 specific appointed times in the Jewish calendar. There are 52 weekly Sabbaths each year. Passover Week includes seven feast days. Then there’s Shavuot (Pentecost), Yom Teruah (Feast of Trumpets), Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), and the seven days of Sukkot (Feast of Tabernacles). The end of Sukkot is celebrated by Shemini Atzeret, the eighth-day assembly. When we add these up, we find a total of 70 of these HaMoyadim.

52 + 7 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 7 + 1 = 70

The Jewish calendar has a heptadic — seven-fold — structure. We recognize that the week has seven days, and the seventh day is the Shabbat.1 There’s also a particular week of weeks, at the end of which the Jews celebrate the feast of Shavuot, or Pentecost.2 The religious year is a week of months, from the beginning of Passover in Nisan to the end of the Feast of Tabernacles in the seventh month of Tishri.3 There’s a week of years as well, and the Mosaic Law required the Israelites to give the land rest after each seven-year cycle.4

After seven weeks of years — 49 years — there was to be a year of Jubilee in the 50th year, and all debts were to be forgiven.5 All land was to return to its original owners, and all slaves were to go free. It was a time, twice a century, when the people of Israel were given a clean slate. Peter uses the phrase “the time of restitution of all things.”6

Hebrew Agricultural Calendar and Feasts

| Hebrew Month | Gregorian Month | Harvest Crop | Levitical Feasts/Other Feasts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nisan | Mar–Apr | Barley | Passover, Unleavened Bread, Firstfruits |

| Iyar | Apr–May | Barley | Lag B’Omer |

| Sivan | May–June | Wheat/Figs | Shavuot |

| Tammuz | June–July | Wheat/Grapes | Feast of 17th Tammuz |

| Av | July–Aug | Grapes | Tisha B’Av |

| Elul | Aug–Sept | Grapes/Figs | |

| Tishri | Sept–Oct | Olives | Yom Teruah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot |

| Heshvan | Oct–Nov | Olives | |

| Kislev | Nov–Dec | Olives | Hanukkah |

| Tevet | Dec–Jan | Conclusion of Hanukkah | |

| Shevat | Jan–Feb | Tu B’Shvat | |

| Adar | Feb–Mar | Purim |

We need to be sensitive to the agricultural calendar as we go through Ruth. On the Jewish calendar, the first month of the religious year is Nisan, in about March or April. That’s when the majority of the Book of Ruth takes place. Barley acts as a good winter cover crop, and it matures about 60 days after it begins growing again in the spring.

This is the time of latter rains, when the barley harvest and the flax harvest occurs. This is the time of Passover. The Feasts of Unleavened Bread and Firstfruits take place during Passover week. The Feast of Firstfruits is always the Sunday after the first Sabbath following Passover. This is a strange formula, but this feast therefore always falls on a Sunday.

The next month in the Jewish calendar is Iyar, during which the dry season begins. Then we get to Sivan in about May and June. During Sivan, the early figs ripen and land tending occurs. The special holiday in Sivan is Shavuot, 50 days after the Feast of Firstfruits.

What is Shavuot all about? We know it best as Pentecost, the day the Holy Spirit fell on the disciples with tongues of fire in Acts 2, the day the Church started. It’s therefore very interesting that it’s the only feast of Moses in which leavened bread is used. It’s also interesting that the Book of Ruth is always read in Jewish communities at the time of Shavuot. When I’ve asked Jews why, they say that it is associated with the harvest. On the face of it, that makes sense. Ruth met Boaz while gleaning in his fields. However, like the Church, Ruth was a Gentile who came to trust in the God of Israel. Like the Church, she was grafted into the family of Israel by marriage to Boaz, her Kinsman-Redeemer. In light of Christ’s role as our own Kinsman-Redeemer, we see there is something far deeper going on here.

The fourth month is Tammuz, which is the wheat harvest. This is when the first ripe grapes appear, in the June-July time period. In July and August there is the month of Av, when the grape harvest takes place. In a culture without refrigeration, there was no way to get grape juice in the spring. It had to be naturally preserved through a process called fermentation. Those who argue that Jesus only drank grape juice and not alcoholic wine are failing to appreciate that by Passover in the spring, the grape juice had to have been fermented into wine. There was no other way to preserve it.

Tisha B’Av — the 9th of Av — is memorable as the day in which both temples were destroyed, hundreds of years apart. Throughout history, a long series of bad things have happened to the Jews on the 9th of Av. The fast on the 17th of Tammuz begins the Three Weeks of mourning that lead up to Tisha B’Av. The 17th of Tammuz also commemorates tragedies that took place on that date, beginning with the day Moses broke the tablets of the Law in fury at the worship of the golden calf.7 The summer has become a time of mourning in Jewish tradition.

Dates and summer figs are harvested in the month of Elul, the August and September time period. Then in September and October, the early rains start and the olive harvest begins. Tishri is the first month in the Genesis calendar, but it became the seventh month of the Exodus religious calendar. With the early rains come the Feast of Trumpets, the Day of Atonement, and Sukkot, the Feast of Tabernacles.

This is a quick overview of the Jewish agricultural calendar. We need to have a grasp of this as we read the Bible, because the people of the Bible were an agricultural people. Little questions like, “Did Jesus drink wine or grape juice at Passover” can be resolved by understanding simple realities about when the grape harvest took place.

Here’s something interesting. If we look for the word HaMoyadim as an equidistant letter sequence, we find it only occurs once in the Old Testament. Statistically, we’d expect it to show up five times, but it only occurs once, and it does so in the book of Genesis. In fact, it shows up at a skipping interval of 70, centered on Genesis 1:14 when the Sun, Moon, and stars are given for the purposes of our timekeeping. Was that an accident? Of course not. It is another one of the strange things in the Bible that give evidence of God’s design.

The Law of Gleaning

As we begin reading Ruth, it is also important to understand the process of gleaning. The Hebrew Scriptures have a great deal to say about protecting and providing for the widows and orphans. One of the ways in which the ancient Hebrews provided for the less fortunate was in letting them glean the fields. In Leviticus 19:9–10 and Deuteronomy 24, the LORD orders the Israelites to leave remnants in their fields and orchards so that the poor and stranger and widow and orphan can have something to eat. In other words, the workers were not to go back over their fields a second time; they were to let the less fortunate pick the fields clean.

When thou cuttest down thine harvest in thy field, and hast forgot a sheaf in the field, thou shalt not go again to fetch it: it shall be for the stranger, for the fatherless, and for the widow: that the LORD thy God may bless thee in all the work of thine hands. When thou beatest thine olive tree, thou shalt not go over the boughs again: it shall be for the stranger, for the fatherless, and for the widow. When thou gatherest the grapes of thy vineyard, thou shalt not glean it afterward: it shall be for the stranger, for the fatherless, and for the widow.

— Deuteronomy 24:19–21

This was the Law of Gleaning. When the professional reapers had gone through the field, they would be followed by the widows and other destitute individuals who would glean the fields. These would gather whatever leftovers they could find to feed themselves. This was the welfare system of the day — God’s way of providing for the poor. Note that the poor still had to work for their food. There were no handouts, except by those providing for their own families.

Naomi is an older woman, and her daughter-in-law Ruth loves her dearly. Ruth goes out every day to glean behind the reapers during the barley harvest, and she brings the grain home to Naomi. The people in town know Naomi, but Ruth is a newcomer to them, and by gleaning for Naomi she earns a reputation for herself.

Gleaning was not always a safe job. It was possible that the young women who followed the reapers might be harassed or harmed by them. However, something very unusual happens. The field on which Ruth happens to glean belongs to a wealthy relative of Elimelech named Boaz, and Boaz notices Ruth. He tells his workers to leave her alone, and he charges her to only glean in his field and not go to another. The plot starts to unfold…

These four chapters represent the greatest love story in history, and in their pages we find abounding treasure. In chapter 1 of Ruth, we’ll see love’s resolve, when Ruth decides to cling to Naomi. In chapter 2, we see love’s response, when Ruth gleans for Naomi. Chapter 3 shows us love’s request at the strange, widely misunderstood threshing floor scene. Finally, in Chapter 4 we see the big climax: love’s reward, in which the land is redeemed for Naomi and a bride is provided to Boaz.

Love’s Resolve

Now it came to pass in the days when the judges ruled, that there was a famine in the land. And a certain man of Bethlehemjudah went to sojourn in the country of Moab, he, and his wife, and his two sons. And the name of the man was Elimelech, and the name of his wife Naomi, and the name of his two sons Mahlon and Chilion, Ephrathites of Bethlehemjudah. And they came into the country of Moab, and continued there.

— Ruth 1:1–2

This is an introductory sentence, which explains the background for the story about to be told. This was the time of the judges, which was not a spiritually high time in Israel’s existence. In fact, the Book of Judges ends by stating its general theme: “In those days there was no king in Israel: every man did that which was right in his own eyes.”8

There was a period after Moses but before Israel was given a king when Israel was governed by a series of judges. It was one of the spiritual valleys in Israeli history. Not a good time. Within that dark period when the judges ruled, however, we find the ultimate love story. It’s a love story at the literary level. It’s also a love story at the prophetic and personal levels.

After taking over the Promised Land under the leadership of Joshua, Israel spent the next four centuries in a disappointing cycle. The LORD would give them victory, but after a time the Israelites would turn away from Him. He would then allow them to be taken over by their enemies. The Israelites would then repent and return to the LORD, and He would then rescue them through one of the judges. Over and over again we see this cycle of events. Ruth takes place during this colorful but somewhat dark era.

When our story starts, there is a famine in the land. A man named Elimelech moves his wife Naomi and their two sons eastward into Moab where there is food.

There are a number of famines in the Bible.9 It’s not an uncommon problem, and famine may be a response to the spiritual condition of the country at the time. God had warned Israel that famine was one of the judgments that would come upon the land as a result of their failure to keep the Law:

…And your strength shall be spent in vain: for your land shall not yield her increase, neither shall the trees of the land yield their fruits.

— Leviticus 26:20

…And thy heaven that is over thy head shall be brass, and the earth that is under thee shall be iron. The LORD shall make the rain of thy land powder and dust: from heaven shall it come down upon thee, until thou be destroyed.

— Deuteronomy 28:23–24

We know there was a famine during the time of Gideon in Judges 6. Israel had again turned to doing evil, so God allowed the Midianites to come in and ravish the land. When the Israelites sowed their fields, the Midianites came in and decimated their crops. This invasion went on for seven years, and the resulting famine covered the entire land of Israel.

This matches the situation in Ruth. The famine must have been ongoing for several years in order to compel Elimelech to take his wife and sons and move to Moab. Centuries before, Moab was born as the result of an incestuous night between Lot and his daughter after his daughter got him drunk.10 The Israelites are therefore related to the Moabites, but there’s no great love between these peoples. Moab hired Balaam to curse Israel during the Israelites’ pilgrimage to Canaan in Numbers 22. Under normal circumstance, the Moabites were barred from participating in the national corporate life of Israel.11 God purposely kept them separate.

Yet, the relationships between some of the individual Israelites and Moabites was good. When David fled the wrath of Saul, he found a friend in the king of Moab.12 The two countries were neighbors, and they enjoyed years of peace.

And Elimelech Naomi’s husband died; and she was left, and her two sons. And they took them wives of the women of Moab; the name of the one was Orpah, and the name of the other Ruth: and they dwelled there about ten years. And Mahlon and Chilion died also both of them; and the woman was left of her two sons and her husband.

— Ruth 1:3–5

This excerpt is from Dr. Chuck Missler’s book The Romance of Redemption, available from the K-House Store.